About My Life

I was born on 8 April 1931, as the first child of two parents from very different families, whose lives were drastically changed by World War I. My maternal grandfather was a county lawyer, and a great patriot who left Szatmárnémeti (now Satu Mare, Romania) with his family. He left his job, his home, and the life of a country gentleman. After the war, he moved to Budapest, preferring the life of a poor refugee over living in Romania. My paternal grandfather, originally a forest engineer became the director of Generali Insurance. My paternal grandparents feared for the lives of their two sons, who were university students. Their older son, György, a student of architecture with an artistic went studying in Munich, never returned from the front. The younger one, Tibor – my father – was a law student. He came home after being imprisoned and wandering in Siberia and finished his studies. Then, his interests changed direction and he qualified as a master builder and carpenter.

My parents were hardened by the life they endured but it could not diminish their zest for and love of life. They often had to put up with financial hardship but were not discouraged by this either. And when traveling abroad was no longer a realistic option, they made new plans: they decided to create a protected little paradise for their three children in Balatonföldvár. The renowned Wellisch architects, Alfred and Andor1, were our relatives. In the 1930s, my father’s construction company built several important buildings, the most well-known of them probably being the apartment building in Eszék Street and the villa in Szirtes Street. He built only smallish cottages In Balatonföldvár, one of which he designed himself in the functionalist style for his family.

The most beautiful memories of my childhood are those of the house in Földvár, the garden, Lake Balaton, and our dog. When I was six years old, I started primary school. I got some beautiful, coloured pencils from my father because I loved drawing line patterns. I remember once standing up in my religious studies class to thank the teacher for the beautiful stories. Then, another time, when I was on my way to school, I told my father that there was a little girl who was going to another religious studies class and the other children were making fun of her because she was Jewish. That is when I learned that my father was Jewish too, and that I was half Jewish. This was the first time I came face to face with this big problem.

I was ten years old when I started at the Catholic Sancta Maria Secondary School for Girls in Budapest. After the cheerful time and freedom of the primary school, the strict feel and all the discipline came as a big change. This was difficult for us but getting used to discipline came in very useful in what we later had to go through. The school defended the conservative Christian values and the guardians of these values soon saved lives. My parents were well aware of this. Official politics had no place in school. After the war, our cultural horizons expanded, which was not possible in a traditional school. However, during the period of terror, the school was a refuge, where they tried to hide several of my persecuted classmates, but they were caught in Arrow Cross raids.

In the spring of 1944, Budapest was bombed more and more heavily. Our mother took us to our holiday home at Lake Balaton and tried to keep everything from me and my siblings. I still cannot put it together in my mind how we lived. Our mother somehow disappeared in the never-ending saga of saving our father. Life in Balatonföldvár seemed like a perpetual holiday: everything was just like the summers gone by, while bomber planes flew over us heading for Budapest, where, in the meanwhile, my dear friend Júlia Gáspár2, with whom I was corresponding in clumsy little writings, had to wear a yellow star. I remember that once my mother’s beloved young brother visited us at Lake Balaton, and while he was staying with us, their house was hit by a bomb, and everyone died in the bomb shelter.

My mother only spent brief periods of time with us. She was always troubled and barely talked, and then she hurried back to my father. In our ignorance and selfishness, we remained carefree and enjoyed each other’s company. We were just children on holiday and did not talk about politics or war. It was almost like we were living a stage play. There were characters who were not classed as Aryan, there were others whose fathers had gone missing in action, and there were those whose fathers were afraid of communists. And all the while, Russian troops were getting closer and closer.

In autumn 1944, we travelled back to Budapest, to our flat at 6 Falk Miksa Street. The bombing went on day and night. The schools were closed, and at night we went to the air raid shelter with our emergency packs. Our father was with us again, but we were very afraid that the Arrow Cross would arrest him. And finally they did. To this day, I do not know how my mother arranged for our father to eventually come back home. We were hiding in our bedroom, and our mother was arranging things in a state of frenzy. On Christmas Eve, the house was bombed, breaking the windows, so we moved down to the bomb shelter. My father spent most of the day in hiding in one of the refrigerators in the Dombai Guesthouse on the floor above us. Groups of Arrow Cross kept entering the house, threatening to disembowel anybody hiding Jews. An ammunition depot right next to us exploded, making the walls of the flat collapse, while the cellar wall cracked, but it remained standing.

Then, suddenly, Soviet soldiers broke open the gate and burst in. My parents were relieved. My father had learned some Russian when he was a prisoner and used this knowledge to save the other people living in the building from brutal violence. The house was declared to be part of the war front. We had to leave the air raid shelter and used planks to carry our luggage, from which the soldiers kept stealing things. For strategic reasons, the Russians evacuated some of the houses on Falk Miksa Street, including ours. We went to my father’s lumberyard because the guard had left his hut empty. It was cold and a long period of starvation followed. But a lot of other people living in the city suffered much more torturous starvation. My growing brother suffered the most. When the fighting ended, my mother and father had the courage to make their way back to the flat on Falk Miksa Street and tried to make the rooms liveable after the damage caused by the bombs and the soldiers. The books on the bookshelf were full of bullets because soldiers had used them as target practice. However, by the time we – the children – got home, it was in a far better state. Spring brought along the stench of dead bodies, and we still had reason to fear violence from the soldiers.

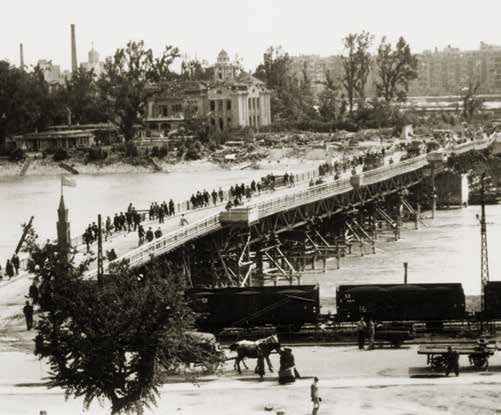

In 1945, after the ‘liberation’, everyone wanted to build somewhere to live, wherever possible. There was no fuel, so my father bought a horse, called Manci3, and we made our way about in a horse-drawn carriage from then on. The lumberyard, which was part of my father’s company, was returned to him, but building materials were in desperately short supply at that time. In the winter of 1949–1950, the Danube completely froze over and people could walk on it, but when the ice melted the connection between Pest and Buda was broken. They used the timber found in the lumberyard to build the first bridge, a pontoon bridge nicknamed Manci, which was used to temporarily replace the beautiful old bridges, which had been blown up.

My cousin survived the labour camp but he was left all alone. My paternal grandmother also survived as my mother’s relatives had sheltered her. The world had fundamentally changed, and many were missing. Those who were still alive came across the bridge.

After the war, we started an art history group at the school, of which I became the head, and Júlia Gáspár its secretary. We visited exhibitions and then discussed what we had seen. With the permission of the nuns, from 1946, I went to the Academy of Fine Arts to do croquis drawing. We drew nudes. It was only later that I got really good at drawing nudes, when I attended the academy’s summer course in Epreskert4. Our teacher was Endre Domanovszky5. When I was at secondary school, I attended Margit6 Gráber’s evening free school for years. She was my mother’s friend and taught useful basic knowledge to me back then.

A valuable book was regarded as a huge thing in those years. My architect uncle, Győző Wellisch7, once gave me a huge, wonderful book about the history of painting as a gift. Uncle Győző also took me to Gedeon Gerlóczy8 to see pictures by Csontváry.

My dear parents invested incredible energies into trying to keep up their desire to live a full life. They had an amazing structure built from leftover, used bricks and the damaged parts of a military barracks in a then completely neglected, sparsely populated part of the rose Hill district of Budapest, above Gábor Áron Street, in Endrődi Sándor Street. They even built a pool under an almond tree in the large garden for us, their three children, as well as for our friends and schoolmates. We would climb trees and started to feel like children again. My mother would jump into the pool before leaving for work early in the morning.

In 1948, the Catholic school was nationalised and renamed after Júlia Szendrey9. New teachers came and we had to study for our school leaving exams with teachers who were unfamiliar to us. Luckily, I passed all my exams.

On 25 March 1948, my father’s company was one of the first companies with a hundred employees to be nationalised, rather unexpectedly. At that time, my father was putting in a great deal of efforts into a major project: the construction of the hospital on Tétényi Road. Lacking today’s level of technology, the project required many workers. He had taken out loans, turned half of our flat into a workspace and bought a new car. Almost everything was taken off him. My parents sold what little was left. We were suddenly poor. I was very much pained to see my parents’ bitter sadness, and to add insult to injury, we were declared ‘enemies of the state’.

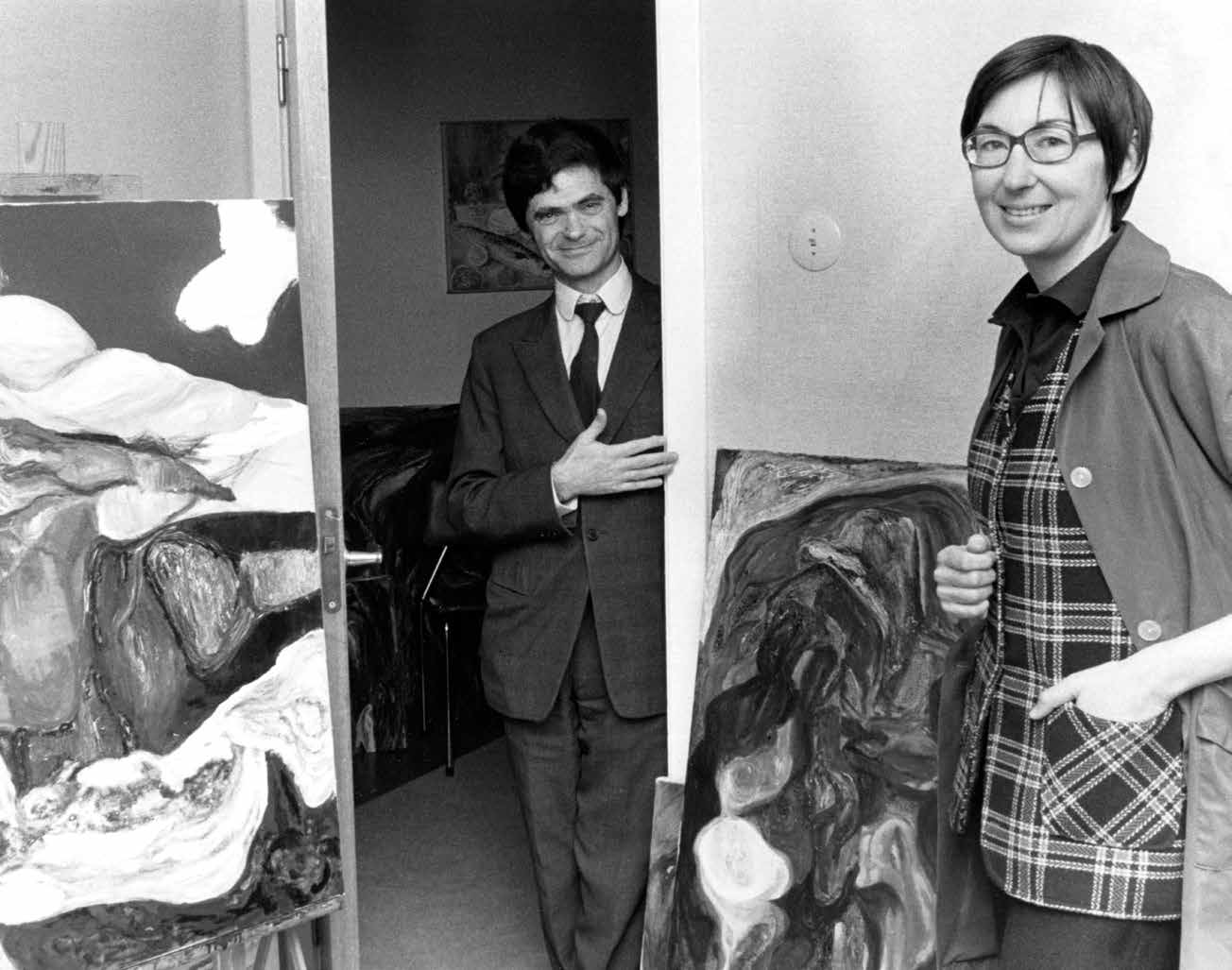

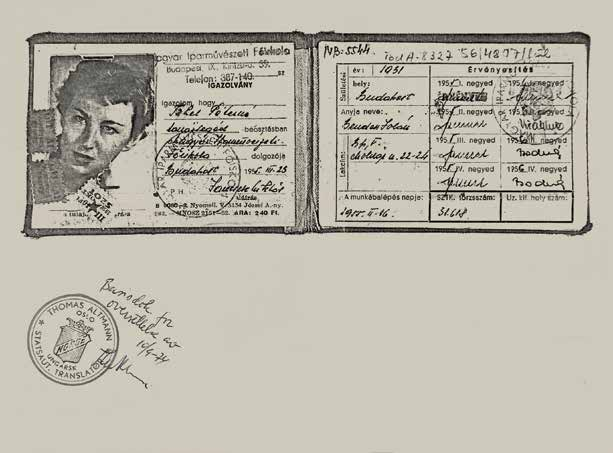

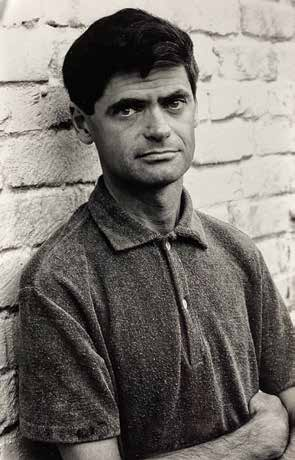

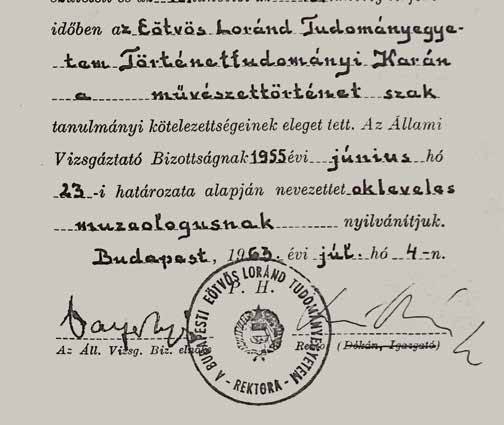

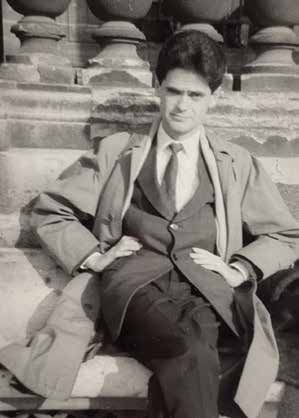

In 1949, under pressure from my father, I applied to the Academy of Applied Arts to study interior design. Fortunately, I was not admitted. The following year, I applied to the Academy of Fine Arts, but instead of allowing me to enrol, I was transferred to the department of museology at ELTE’s Faculty of Humanities. I was disappointed, but I actually wished to study museology as well. In the first year, we had basic ethnographic and archaeological studies. I met Péter Tehel, an assistant professor in art history, who taught there. Meeting him was the most important event in my life as he became my life partner and best friend. I approached my classmates cautiously, because fear and having to hide had left their mark on my personality. At university, I made lifelong friendships that brought me a great deal of happiness. When Péter and I visited home, it was always nice to meet friends we had not seen for a long time.

Peter and I got married without any of the usual formalities. We moved to a rented room in Szentendre. then my parents set aside side=“left”, a room for us in their flat on Falk Miksa Street. After that, in 1955, we moved into a one-bedroom flat in Molnár Street. We painted the walls in bright colours in the spirit of my husband’s ‘sinful, modernist’ approach. On Tuesdays, we would receive visitors and supply them with cheap biscuits and heavily watered-down tea. We did not have much money and we had loans to pay off. Some of the guests were from my husband’s university circles, while others were obscure, unrecognised artists. Peter secretly took his favourite students to his old friend, Endre Bálint10. That is when I met Dezső Bokros Birman11, Lili Ország12, and Dezső Korniss13. Korniss was our neighbour on Molnár Street. We would often visit him, and he always expected us to admire his pictures standing on the easel.

In 1955, I was taken on as a lecturer at the Academy of Applied Arts, where I was the youngest teacher. The job was everything I had wanted, and the academy’s administration allowed me to attend the drawing classes of the students.

I was more personally involved with two important buildings in Budapest: the Opera and the Parliament building. After completing my secondary school studies and my unsuccessful attempt to enrol at the academy, I took up a position as an unpaid intern at the Opera House. This was through my sister, who was a student at the Ballet Institute. I loved the masks and the life behind the stage. I would have needed to be qualified as a hairdresser to become a key make-up artist, but I did not want to do this. From 1951, I worked as a tour guide in the Parliament building with two of my classmates, Margit Egri14 and Edit Wurst15. There was much a great deal to see and show in this wonderful building. I often felt quite moved escorting ordinary people up the dizzying stairs and seeing how impressed they were. But there were also some less friendly tours, with political delegations being protected by armed escorts. I published several articles, for example in Szabad Művészet [Liberal Art]16, on the pictures of Aladár Illés Edvi17, as well as the colourful woodcuts of József Domján18 and the mosaics of Eszter Mattioni19. Before these articles were published, I had to present them to Zsuzsa D. Fehér20, who wrote notes with a political content between my lines; this was very hurtful.

In 1956, together with my friend Margit Egry, I wrote a little book21 about the history of the Parliament building, which was full of illustrations and black and white photographs. In October 1956, my students and I marched in protest in front of the Parliament building, from which lethal shots were fired at the crowd. My husband was fearless amidst this crisis, while strangers came and went in our flat. He even had a rifle given to him, even though he was always averse to guns. Sometimes he did not even come home. He worked a lot in the Fészek Art Club, in his library and in the Association of Hungarian Creative Artists. Everything around us had changed. I was new to the Academy of Applied Arts and would listen in silence to stories about various grievances, similar to those I had experienced myself. I took part in the big demonstrations marching among huge crowds of people.

The suppression of the revolution was followed by reprisals and punishment. Several people warned us to try and leave the country, but we left it too late and the borders were closed. In the summer of 1957, we finally received the passports that we had applied for a while back but were only allowed to travel to other socialist countries. We decided to try to get to the West through one of these countries.

We went to Prague as the guests of a Czech art historian. We did not dare to go back to Budapest so instead travelled on to Poland. The war had devastated Wrocław and at night armed robbers prowled the city. Since it was dangerous to go out into the streets, we slept at the railway station. Warsaw welcomed us with a thriving culture and free, daring exhibitions, but there was a terrible shortage of food. Everyone was kind and good to us when they heard that we were Hungarians.

We returned to Prague and got a one-day transit visa from the Austrian embassy there. They said it would not help us to escape to the West but we could try. Peter’s escape plan finally worked: thanks to underinformed border guards at a small border post in Czechoslovakia, we crossed over into Austria. We went to the police in Vienna and served the two-week prison sentence that was mandatory for people like us in those days. The Austrian police were already afraid of spies, and our escape was a suspicious one. After two weeks, we were transferred to the refugee camp in Schwechat. We contacted our former colleagues from university, among them János Dobai22, Kati Dobai, as well as Péter Meller23 and his wife24, and they visited us in the refugee camp. In late summer 1957, I went to take the entrance exam in model drawing at the Akadémie de Bildenden Künste Wien with a high temperature. They liked my drawing and I enrolled, and even got a scholarship. Péter received a Rockefeller grant at the art history institute of the university. Through a virtual miracle, we also got a place to stay at: we were accommodated in an old villa in Vienna, destroyed by the war. Instead of a bathroom, we used a tin bathtub. Charity organisations gave us some furniture. And we had a little garden, too.

A very good period of our lives ensued, but it was a big blow to me that I had to leave my mother tongue behind. I spoke German well, and it was to my great advantage at the Académie. I started learning German in my childhood because my siblings and I had a German governess, Muci, who was like family to us when my mother fell seriously ill after the birth of my little sister. My father set up a small home for her in the house in Falk Miksa Street. So I could speak but not write well in German. In Norway, not knowing the local language, I had neither the oral, nor the written skills.

We had a good life in Vienna. I was extremely satisfied and happy. I set off early every morning to find the best spot in front of the nude model. Professor Robin Christian Andersen25 liked my huge charcoal drawings. The greatest praise I received from him was that once he said that he drew just like me when he was young. He kept mentioning Cézanne. In the next year, Professor Pauser26 took me on as one of his few students. He was a very good teacher and paid attention to the personalities of his pupils, rather than just looking at them to see reflections of his own art. In 1958, I won the recognition of merit called Fügerpreis.

We had many visitors, including artists and art historians, in our ‘little bohemian nest’ in the old villa, which we had been renting since 1957. We temporarily put up those people here who had no place to stay. Among them, we were visited by Péter Meller and his wife, Marika. In 1958, Korniss was a guest of ours here, after his exhibition in the Netherlands.

In the evenings, we would listen to life stories accompanied by some Vingas wine. Food played a secondary role. Our guests were mainly Hungarians but there was a peculiar Austrian woman, who I also made friends with and she sat for me for free.

I was fascinated by the museums, exhibitions and palaces in Vienna. In 1958, Péter and I began our travels by interrail and/or hitch-hiking. My husband was a very competent and tireless driver. Our first trips took us to Italy: we went to Venice, Ravenna, Bologna, Florence and Rome.

Then our beautiful life in Vienna came to an end. Our scholarships were only for two semesters. The city was full of Hungarian refugees so we had to look for another country that would take us in. We could have gone to the United States but we did not want to leave Europe, once we had finally found it. I was offered an amount equalling four months of my scholarship at the academy to join the last transport to Norway, so I said yes.

We arrived in Oslo in spring 1959. After glamourous Vienna, the city seemed plain. By now, it has changed beyond recognition. At least to me it is unrecognisably different.

Summer arrived late but when it finally did, we were dazed by the beauty of nature that entwined the city. Wooded areas, lakes, fjords sprawling endlessly. The elderly couple who we rented our place from treated us as if we were their much-loved relatives.

Many people were willing to speak the otherwise very unpopular German language for our sakes. Then we started learning Norwegian.

I slowly managed to explore the extensive activity of Edward Munch. I had admired reproductions of his graphic pieces since my secondary school years. Winter set in and teaching started at the academy. The scholarship only offered a relative financial security. Professor Alexander Schultz27 addressed me in German. This refined and erudite professor wanted to talk to me about Matisse. He viewed my paintings with a certain reservation.

After the four semesters, but even before that, in the holidays, I needed temporary work, so I started painting portraits, about good-hearted and patient women and men. Some of these turned out extremely well. My wealthy patrons regarded me as their friend and supplied me with everything I needed. Years later, an elderly lady phoned me and asked me to visit her. She showed me into her beautiful house, where a small home altar was standing, bedecked with flowers and with the portrait of her husband hanging at the top. “This is the most living memory,” she said, “that is left of him. Thank you.” The hardest job for me was to paint impatient, forever fidgeting children.

At the academy in Oslo, Frans Widerberg28, who was working next to me and soon earned recognition as an artist, made a major impression on me. He drew my attention to a Norwegian painter, not quite recognised at the time: an artist based in Stavanger, called Lars Hertervig29.

Then a huge change took place in our lives: we had our own studio and flat. This sculptor’s atelier had ample natural light and not all the modern conveniences. It was the only studio in the new residential quarter, in Lambertseter, on the edge of the woods. The flats with balconies provided modern and comfortable homes for those who moved here from the town’s poor and dilapidated houses.

Finally, I was able to paint in my own home. There was a generous man, the owner of a paint factory, who allowed me to buy what I needed from his excellent shop in exchange for making portraits of his four children. I managed to get hold of all the supplied that I needed, including the finest art paints. I felt rich and free. In the woods, sitting on the ground, I painted the undergrowth. These pictures were very popular and I soon found owners for all of them. I carried decayed, bizarre-looking and creature-like tree roots into my studio. That is when I painted the series titled Dance of Roots.

I organised a celebration on the occasion of having my own studio, where I invited my colleagues from the academy, and it was too successful, so to say. Many guests came and they were not very sparing with the drinks. The other residents of the block were not too pleased. But we were very popular with the children who lived there. I was able to practice portrait painting on impatient, beautiful little models, for modest prices.

We wanted to exhibit our art abroad so we set our eyes on Paris. We travelled to explore Paris, the capital of the arts, on two occasions to build relationships and experience all that so many artists expected of it. It was my husband who created the opportunity for the exhibition in 1960 in the Centre Culturel Hongrois30. Péter, back in Budapest, was already establishing ties; many Hungarian refugees lived in this beautiful city.

Unfortunately, I have few memories of the joint exhibition with my husband. Somebody wrote nice words of praise about our pictures in the France Soir31, but not in the art column. The exhibition was organised by a Hungarian art historian living in Paris, Kitti Wolf Fazekasné32, who my husband had known from university. We had to leave the exhibition to catch our ship. We made the voyage from Kristiansand to Rouen on a Norwegian cargo ship, thanks to the patronage from a rich lady from Oslo. I cannot deal with stormy seas very well, so I was ill for two days after we disembarked.

After the exhibition was dismantled, Kitti Wolf took the pictures to her hotel room, and since she could not settle her bills, the hotel confiscated all her belongings. My pictures disappeared and they have not turned up ever since. Then a letter of complaint was sent regarding the behaviour of the art historian lady, and we later found out that her mind was not sound.

The second time we travelled to Paris was in 1961, when we took a big bundle of pictures with us on a train. We temporarily let a colleague of ours from the academy use our studio. A long sojourn in Paris followed, full of amazement and awe. Unending visits to museums and exhibitions. We found out only little about fine French cuisine as we mostly lived on chips. At night, mice were running across us in the cheap hotel in the Cartier Latin. We visited Endre Bálint in Paris. His had a problem with his lungs and was in hospital. He had a room to himself, filled with his pictures. We got to know the head doctor and his family, who were very supportive of Endre Bálint. We spoke French rather poorly but were trying to practice.

Our money was running out, but my husband was browsing books and periodicals on the banks of the Seine. He bought large and heavy issues of L’Illustration33, which I was not happy about. But later I used the illustrations from these for my graphic pieces.

Without connections and patrons, our situation was hopeless and without prospects, so we could no longer stay in Paris, but instead of going to Oslo, our journey took us to Bern. Péter’s fellow student at university, a historian of ancient cultures, Tamás Pekáry34 invited us to go there. He lived in Bern with his wife and worked at Bern University. They had an attic room, where they put us up. Our knowledge of German was a blessing again. It enabled us to do work. We collected material for the Swiss art encyclopaedia. I made illustrations on the theme of ancient cultures for the professor, and I renovated old drawings in an architect’s office using new methods. The lines in the old architectural drawings were faded, and the paper was patchy in places. I took them and put them in a copy machine, lit it and pulled the graphite- powdered metal plate from underneath. The forms of the drawing’s old parts, the black lines and the textures but also the mistakes, were transferred to the plate. Using cotton wads, I carefully removed all the staining from the plate, which was then ready for a proper photocopy to be made of it.

We travelled to Zürich, where we managed to build contacts. The exhibition at the Atelier Chs. Mosimann (Zürich, Froschangasse 3) was not a great success but another gallery in Zürich also displayed some of my pictures. Then, in 1962, we took a large part of the paintings home, to Oslo.

We travelled around in Europe without citizenship, carrying a passport with this status in it. Leaving Switzerland, we finally returned home to our studio in Oslo. A new and difficult period ensued.

I painted pictures during the day and went to a faraway factory by a dark cemetery to make plated skirts in the night shift. Péter worked as a watchman in a shipyard. I also worked in a photocopy workshop, inhaling suffocating ammonia. My boss dismissed me because I was reading Ibsen dramas in the breaks, away from everyone, but he would have liked to make me an overseer. I was also employed by an ice-cream factory, on a conveyor belt. One day, I collapsed in the deep freezer chamber and told my overseer that I was pregnant. He was an extremely good person, and he was also living in the new residential quarter, by the woods. He gave me a lift every evening. In the mornings, he and his wife would have their morning coffee on the terrace. He enjoyed talking about the new, beautiful life of workers. He had a festive attire made for his two daughters for the Norwegian national holiday35. And then I thought that this country should be the home for my child to be born in.

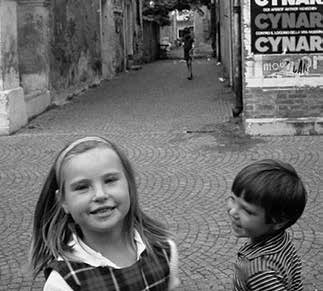

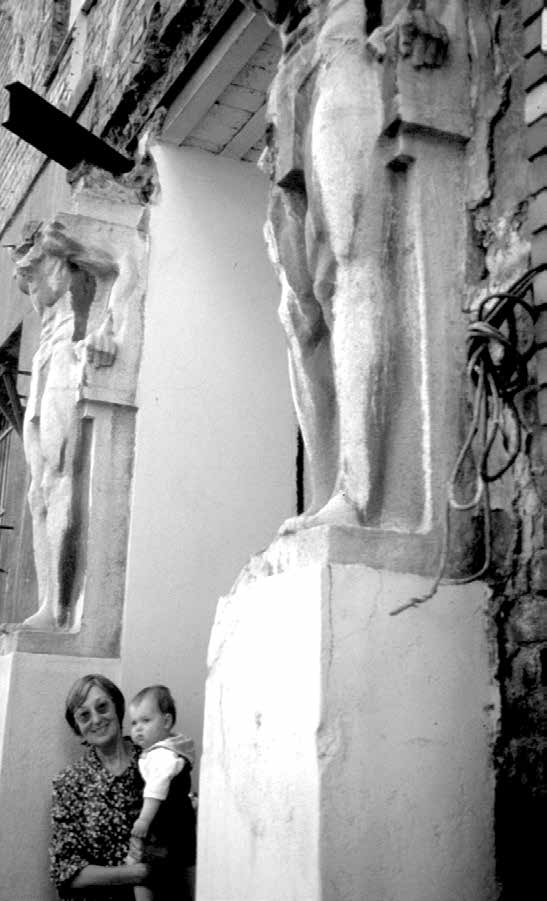

I virtually went to the hospital with a paintbrush still in my hand because we were painting the walls of our new one-bedroom flat. And then our little girl, Pauline, was born. After that, everything changed, including our personalities and way of life. While I was expecting her, I was afraid and protective of her. In the pictures of my Superficies series, the large white and pale-toned newborn beings are threatened and attacked by huge, aggressive, dark forms. In 1962, world politics, the cold war, was a threat, and many bad memories were haunting me. After Pauline’s birth, the daily chores took my mind off these things. Happiness and wonder filled our days. Our little girl attended the nursery in the woods for six months. I painted portraits. I copied and painted old architectural drawings. Then I was pregnant with our second child and our son, Per Jacob, was born.

A new life began for us in the company of the two wonderful beings: somewhat isolated but making us truly happy. I admired and was at the service of my children. It was a beautiful time of my life.

Our family in Hungary was at an unreachable distance. My father, increasingly ill, tirelessly wrote his ever longer letters, any from my mother were lines saying she was missing me. People who left the country illegally were awaited with a prison sentence behind the Iron Curtain. My mother-in-law visited us several times in the sixties, being my support, and it was joyful to share our experience of raising our children with her.

In 1966, I resumed my working life, which came with a radical change in my lifestyle. I worked in the Riksantikvaren, the directorate for cultural heritage, for four years, and was in connection with architects and art historians. I spent my days in a dark room, amidst chemicals and machines. I had to manually create pictures suitable for publication from old glass plates and poor-quality amateur photographs. My children went to kindergarten, and at times they were coughing all night, but I had to focus on my work in the dark room. At the end of the fourth year, I was given a farewell party in our studio by my colleagues, archaeologists and art historians, who brought lots of valuable paints as gifts. Twenty-five years later, they all came to my exhibition in Oslo, and several of them bought my paintings. It was really nice to meet them again and chat.

Travelling was an important part of our lives, but now, with the children, we went from one country to the next not by Interrail and hitchhiking but by car. We had an old Citroën, which Péter drove, and he organised the trips. We visited museums, churches and exhibitions from Madrid to Naples. We stayed in cheap guest rooms in small villages and made many friends. We drove to the Netherlands, Belgium and London, too. We saw the prominent European exhibitions, the Venice Biennale, the Documenta in Kassel, on several occasions. Having the children meant more relaxation during these travels: we swam in the sea or the lakes and spent half a day in the Zoo in Rome. Pompeii, a living city once covered by lava, was a great experience for the children; they talked about it for years.

Then the children grew up and we bought a better car, so Péter and I continued our explorations for a long time.

Péter worked at the heritage management office in Oslo as an urban historian. In 1970, he was offered a teaching position in Stavanger. Later, he taught art history and drawing in two schools. Then, I took over his drawing lessons, under the name of Colour and Form. We moved into a spacious rented home, and a year after that we bought an old, three-storey wooden house in need of renovation. The rooms had lots of space, so I immediately started painting.

We continued our travels in the summer holidays. In 1971, we visited the Dürer exhibition in Nuremberg, which had a great impact on me. Upon returning, slowly nurturing my plan, I started working on two large-scale pictures: Sarcophagus in Rome and Mantegna-Dürer Variations. It took me a long time to complete them, and I never had the chance to exhibit them in Stavanger. Their debut was in 1990, at my exhibition in Szombathely, Hungary. I wanted to fill my devotion to some of the periods of early art with something personal. I felt that artistic freedom allowed me to do that. In front of the canvas, I was left alone with my memories. The friezes were filled with suffering and hate.

The large, old wooden house with the big garden provided a safe and peaceful life. The primary school was next door, and the other schools were also within walking distance. The garden was full of organ bushes, a rose arbour and soon a new addition was made to our family: a labrador. We had had animals before that too: guinea pigs and cats. It was possible to play football nearby and three houses down there was a tennis club. Amidst the many nice memories, we only had one terrible experience, when our daughter was hit by a car once on her way back from horse riding. Fortunately, out of fun, she kept her horse-riding helmet on, so she only suffered a severe fracture in her leg. The Poor thing had to stay in hospital for weeks.

We had lots of everything: plants, animals, projects. The props changed in the house as the children grew older. What remained permanent was the ever-increasing volume of Péter’s books and the increasing number of my pictures. In the realms of my studio, converted from a cellar and slightly illuminated through the street windows, I projected pictures onto a large canvas every day, late into the evening, and I was painting, with different music playing in the background. No one saw these pictures. Péter saw my paintings and was certain of their value; he supported me throughout. My life would have been inconceivable without him.

We came home with the children in 1967 for the first time. At the border, we were greeted by weapons pointed at us. Our little boy was sobbing quietly, and our daughter asked Péter: “Did these people know that Norwegian children were coming?” Waiting for the visa, our son started playing football with the border guards. “The reason for our visit,” we said, “was to visit our grandmother.” I had lost my father by then. We stayed at my younger brother and his wife’s place. The children were happy to experience that they also had cousins like other Norwegian children. We looked up our friends with caution because we could not know if we were still considered as dangerous enemies.

The children went to summer camps to learn their mother tongue. They did not pick up anything at all but they learnt many English words from the children of the other émigrés. Our son taught the other children how to play ping-pong.

Péter and I took lots of walks in the city, and I took plenty of photos, collecting material for my paintings. In the basement of our big wooden house, I projected these images on slides, and they assumed new life as paintings, stripped of their original setting and incorporated into my personal life. This became my world; I painted these pictures for years.

We wanted to be closer to Hungary and be able to spend more time there in the summers. In 1983, we bought a plot of land in Sauerbrunn. Sauerbrunn, or Savanyúkút (sour well in Hungarian), is a resort in Burgenland, rich in minerals and named after its sour-tasting medicinal water. We began building our little wooden house in one of the new plots of the resort, on the edge of the woods. A train ride from the Hungarian border got us to Savanyúkút. We wanted it to be a place where we could welcome our relatives and family. My paintings also had a home here. Does and bucks came up to the edge of the garden. I did gardening and hosted the guests, from Norway and Budapest alike. Many of our old friends came to see us. Éva Körner36, who, after the great times we had spent together in our youth by Lake Balaton, enjoyed swimming with me in the little lakes here too. Péter’s old friend, an incurably committed urbanist, János Frank37, only ever made it to the local little restaurant, where he obtained new experiences about Austrian wines. Lajos Németh38 and his family came on hikes in the woods and bathed in the lakes with us since they were genuine nature enthusiasts. For many years, Péter and I spent the two months of summer holidays here.

In 1988, I stopped being secretive about my art and I debuted with my pictures – inspired by Budapest but painted in Stavanger – in my hometown, Budapest. All the pieces of the Silent Witnesses theme, i.e. the paintings, prints, drawings and collages, were made in the old wooden house. The pictures I sent to the Norwegian national exhibition were rejected twice, so after that I gave up.

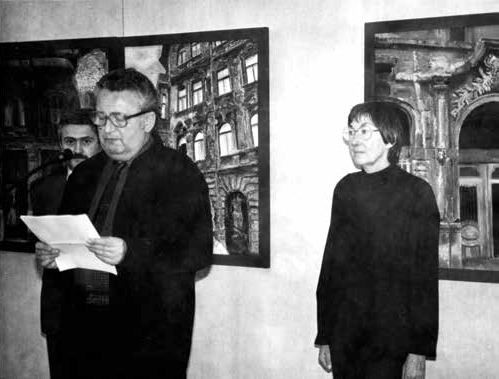

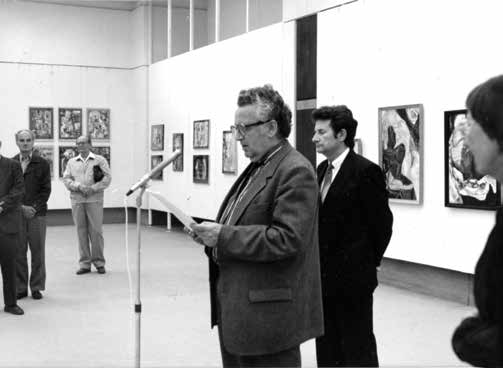

I was 57 years old when Lajos Németh opened my first significant solo show in Újpest, Hungary. His review was published in the periodical Szabad Művészet. Lajos deemed my pictures valuable, and his encouragement meant a lot to me.

In 1990, my largest-scale exhibition in Szombathely, Hungary was also opened by Lajos Németh, and his article was published in Új Művészet [New Art]. A year later, another show of my art opened in the Collegium Hungaricum in Vienna, opened by Ilona Sármány39. Besides the theme of Budapest, the works displayed at these shows also included motifs I collected in Burgenland and in Vienna, which afforded me new opportunities to weave the threads of my imagination about a bygone world.

The recognition my work received in Budapest was important to me, and I carried on painting in Stavanger.

The head of the Kunsthalle in Stavanger, a half German sculptor, Roland Lengauer40, came to my studio upon my invitation. Finally, in 1993, I had the chance to have a debut in Stavanger. I was 62 years old. I had organised several exhibitions of my students’ works, and now I was able to present my art in the great hall of the Stavanger Kunstforening: I exhibited Silent Witnesses. The distant theme of the exhibition Tause vitner [Silent Witness] aroused unprecedented interest. The exhibited material comprised my Budapest pictures and the ones I painted in Vienna. The review was one of praise and understanding, drawing in many visitors and many purchases were even made. Two years later, I exhibited a part of this material in Oslo. Representatives of Hungarian associations brought small Hungarian flags and sunflowers to the opening. Many of my old colleagues from the directorate of cultural heritage also came and I met some of the sitters for my old portraits. The success of Tause vitner urged me, to seek a new theme 23 years after I came to Norway.

Konsgård, the school where I had taught for many years, is a prominent centre of Norwegian cultural history. Two of its alumni are now highly acclaimed figures of Norway’s literary history: Alexander L. Kielland41 is a writer and Sigbjørn Obstfelder42 a writer and poet. Behind the school there is a Romanesque-Gothic cathedral, which is an important Norwegian listed building due to its delicate details and intact beauty.

In the following year, in 1994, I exhibited my pictures in the Galeri Koloritten, a private gallery in Stavanger, under the title of Konsgård ulenfor hverdagslyset.43

I wanted to show the architectural ensemble in Konsgård in an unorthodox light: I wanted to highlight and emphasise its importance in art- and cultural history. I was drawn to its beauty of form, its stone base, stonewalls and the stone church behind it with the old trees and a lake.

In the 1990s, I took a new direction in my painting. I discovered nature in Norway, which I had admired before too, but I looked at it with new eyes: the stones came to life. Around me, there were / are these frightening, wild landscapes, the bewildering rock formations. I walked among them; I touched them. My daughter and our Labrador were my guides. New pictures were born in my studio. I taught fewer lessons and painted more.

I stopped my evening courses to be able to devote more time to painting. In the meantime, my eyes had to be operated on several times. I was terrified of going blind.

I first exhibited my rock paintings in Norway, in 1997. The venue was in an old building, in an environment with a rocky coast, The show titled Stein, mounted in several rooms of the Hå gamle prestegård44 attracted many visitors and many of my pictures were bought; moreover, I was later contacted by several people, who wanted to buy paintings with a rocky theme. I stopped teaching altogether at this point as old age was already lurking around me and I wanted to paint more. My paintings were inspired by fear and wonder. I think I perhaps managed to express the feeling of fear in my Lava triptych.

In 1998, we left Austria and bought ourselves a small summer home on Budapest’s Rose Hill district, in Kapor Street, which we then gradually converted into our family abode. The place, which was originally a caretaker’s flat, was transformed into an artistic building. In the meantime, our first grandchild was born, and then two others: Sindre, Hallvard and Olav. I devoted myself to being a happy grandmother.

My son and his family came to Budapest in the summers, saying that Hungarian pasta was tastier than anything else and that their grandfather was an excellent chef.

The Palatinus and Dagály swimming pools of Budapest proved to be a greater experience than the natural lakes.

My fondest memories are the times we spent together with my old fellow students from university and my friends. Then it was fewer and fewer of us. Our daughter brought Norwegian guests to our place, and they were amazed by our walnut tree and the diversity of birds in Hungary.

Our old wooden house in Stavanger was in a bad state of repair, and we sold it in 2003. Our daughter bought herself a small wooden house in the next town, Sandnes, while Péter and I purchased a flat in the centre of Stavanger. We needed to select what we needed: drawings, studies and the pictures we deemed to be of poorer quality were doomed to be chucked. Some of my pictures had room in the cellar of the new flat. Many other paintings were in our home in Kapor Street. Péter grew ever more ill and needed full-time care. Moving house would have been impossible without our daughter’s help. My last pictures titled Coal and Ashes, were still painted in my studio. I also did painting in Kapor Street and in the new flat in Stavanger, but less and less.

In 2017, I tripped in the Kapor Street house and fell. My shoulder had a fracture, and my arm was paralysed for half a year. Pauline brought me home to Stavanger. I ‘escaped’ from Budapest, the life I had grown used to, for the second time. I left all I had there. My pictures, a significant part of my life’s work, remained in the corner of the studio. In 2020, we sold our home in Kapor Street, and my pictures were put in storage.

During that period, I was not capable of picking up a brush, and had to struggle to stay physically independent. When my situation finally improved, an inconceivable blow was dealt to us: our son was diagnosed with a serious, incurable illness. Growing old, with a worn-away body but still having enough strength to feel miserable, I tried reviving my limbs. It seemed that I had lost myself.

It was a phone conversation with faraway Budapest that brought me new life. I owe infinite gratitude to Katalin Németh, who came to the rescue. She invited art historian Katalin T. Nagy to my studio, who, with her incredible enthusiasm, began to familiarise herself with and systematise the pictures I had left in the studio. The concept for an exhibition was also drawn up. Instead of illness and death, my head was filled with the delightful thoughts of titles, dates and dimensions.

In 2020, Katalin T. Nagy organised an exhibition of my pictures in the San Marco Gallery in Óbuda. She also held a precious and interesting speech, which I was able to follow online, and my friends and relatives also sent me photos and recordings of the event. I experienced this joy and honour in hospital, but one does one’s best to get better. And I did my very best.

Slowly but surely, the concept of this book was taking shape. It is also to Katalin T. Nagy that I owe this book about my life, my oeuvre and the reception of my art. Her work as curator and editor was made even harder by my bilingual environment, and having to collect and catalogue my pictures, which I made in two countries, and which were scattered in several. I personally was happily to hide behind the various tasks; it was not easy for me either to find my way around in the past. My life and activity can be traced back to a historic distance in time, as I am very old. It is not easy to recall historical and social dimensions that are no longer relevant to our present time, neither is it easy to remember people who are long gone, my friends, and my long life with so many twists and turns.

After a year of struggle, our son died in 2023. The year after, Péter also died. In 2024, my daughter pulled me out from my utter darkness, and took me to Budapest. The last time I had seen my hometown was seven years before that.

I was able to meet Katalin T. Nagy in person. I can honestly say that keeping in regular contact with her over the years has kept me alive. She has given me a mission to stay alive. Travelling to Budapest seemed to me an unlikely event. And it is a peculiar feeling to still be alive.