Katalin T. Nagy

“In me the past falls like a stone“

The Art of Judit Wellisch Tehel

Born in Budapest in 1931, Judit Wellisch became known to the art world both at home and abroad as Judit Wellisch Tehel. The name she adopted, Tehel, came from her husband, Péter Tehel. She often signed her pictures with her initials: JWT. The purpose of this book is to outline and present her painting and graphic oeuvre, with the works divided between Hungary and Norway. I grouped the works in each chapter around a different artistic idea, although they are intrinsically related, built on each other and draw inspiration from one another. The groups of works and the periods are not distinct from one another either. The five chapters – Nature, Architecture, Anatomy, Stones and Paperwork – are organically interconnected and overlap in time.

The painter tells the story of her adventurous life, replete with dramatic events, in her autobiographical writing, bringing the artist closer to the readers and helping them to better interpret her works by sharing important events. Her entire oeuvre was significantly influenced by what she experienced, her anxieties and fears, as well as joyful discoveries and wonders.

The artist’s childhood was dominated by the horrors of World War II, while her youth was defined by the oppressive atmosphere of the 1950s. Then, after she left the country of her birth, she found a new home in a foreign country and brought up two children with her husband. While she devoted more and more of her energies to painting in the 1960s, it was only in the 1980s that she first exhibited her pictures linked to Budapest but painted in Norway.

From 1984, the family would spend their summers in a small house in Sauerbrunn, Austria, and later they bought a flat in Kapor Street, in Budapest’s second district, which became their base in Hungary. Judit began to paint less and less in the 2000s and due to Peter’s illness she travelled ever less frequently to Hungary, finally stopping going there at all.

Judit studied at the prestigious Catholic Secondary School for Girls2 run by the Congregation of Jesus in Budapest, from where she graduated in 1949. She was interested in drawing from an early age, and she attended special classes with the permission of the nuns at the school. In the summers, she did drawing at the free school of Margit Gráber3. After completing her secondary school studies in 1949, she tried to enrol at the Academy of Applied Arts to study interior design and furniture design, but was not accepted. She, therefore, trained herself by going to the Epreskert studios of the Academy of Fine Arts to draw. She found a job at the Hungarian State Opera, where she worked alongside a mask master. Masks were to play an important part in her later life, and, albeit only decades later, the carved masks on the façade of the Opera House would even appear in her paintings. In the following year, in 1950, she tried to enrol at the department of painting at the Academy of Fine Arts, but did not end up studying there since she was transferred to the Faculty of Humanities, where she studied art history and graduated as a museologist. By a strange twist of fate, she later became an assistant lecturer teaching art history at the Academy of Applied Arts. However, she did not give up on her artistic ambitions, and after teaching her lessons she would join her class to draw as a guest student.

In addition to teaching, she and her friends, Margit Egry and Edit Wurst, held guided tours in the Parliament Building, mostly for groups visiting Budapest from the provinces and for other members of the public who were invariably impressed by their visit to the country’s most famous symbol. These guided tours resulted in a small book, titled The House of Parliament, published in 1956.

In the meantime, she married a fellow student, Péter Tehel, who was also an art historian. One of their wedding witnesses, their friend János Frank, also became an art historian. For a while, the couple lived with Judit’s parents before moving into their own flat in Molnár Street in the fifth district of Budapest in 1955. They lived close to Dezső Korniss and Endre Bálint, with whom Peter nurtured a close friendship. As an art historian Péter was interested in painting, and also did some painting, mostly abstract pictures, which was strictly forbidden at that time. He took an active part in the Revolution of 1956, and in the aftermath, despite being advised to leave the country while the borders were open, nevertheless stayed. In 1957, when retributions and imprisonments were in full swing, the Tehels were warned by some well-intentioned people about being potential targets. In the summer of 1957, quite miraculously, Judith and Péter received passports valid for entering other communist countries. They travelled to Poland and from there to Czechoslovakia, where they went to the Austrian embassy in Prague and applied for a transit permit to Austria. With another stroke of luck, they were granted the transit permit, and although they were told at the Austrian embassy that this would probably be of no use to cross the border, they tried anyway and made it to Austria. Since it was just a small border crossing, the guards had most likely not seen such a document before and allowed the couple to pass. A new life began for them, replete with both happiness and difficulties. In the autumn of 1957, Judit applied for admission and immediately enrolled in the painting department of the Akademie der Bildenden Künste in Vienna. One of her masters was an adherent of Cézanne, while another regarded Matisse as a genius of painting. This served as a good foundation for Judit as a painter looking for her way, but her intentions led her down a different path. She and her husband did not want to stay in Austria, and when the opportunity arose, they headed for Oslo. In 1959, after being admitted, Judit continued her studies at the Kunstakademie in Oslo. The art training she had in Vienna and Oslo had scant influence on her as she deemed her teachers to have been too conservative.

The couple had to take on various jobs to make ends meet, and difficult years followed. Sometimes they had to work in factories, and sometimes Judit’s portrait commissions added to their income. In the meantime, she was able to display her new works at exhibitions in Paris and Zurich, which received good reviews but brought little in the way of money. In 1963, their daughter, Pauline, was born, and a year later their son, Per Jacob. Judith then got a relatively good job with the Norwegian Riksantikvaren, the directorate for cultural heritage, where she worked as a photo assistant and retoucher for six years. Whatever her circumstances and state of mind were, she would always paint in the evenings. Then, in 1969, two teaching positions were advertised at the school in Stavanger, which Judit and Péter won. In 1970, the family moved from Oslo to the coastal city of Stavanger, which comprises part of the mainland and several islands. Judit taught drawing and art history at the prestigious Katedralskole in Stavanger for over two decades, until her retirement in 1995. Peter taught art history at several schools in Stavanger until he retired in 1994.

Judit Wellisch’s painting developed only slowly, as she pursued her personal and artistic quest simultaneously. Her painting of the first two decades was inspired by what she saw and learned of Europe’s artistic heritage. No longer restricted to Hungary, she was able to travel around Europe, visit major museums and study works, which she mostly only knew from, poor quality black and white photos. Initially, abstract expressionism impacted her profoundly: her motifs were organically inspired and had an intense emotional charge. The living organism of her pictures were increasingly combined with surreal associations. The outstanding work of this period was the series titled Dancing Roots. Her series from 1962 titled Superficies is dominated by organic shapes, but some body parts, such as an arm, appear alongside them. While the word Superficies refers to the outer appearance, shell or surfaces of things, what we see in these pictures rather evokes our innards, viscera, or internal organs. These pieces present an inverted world: if this is the surface, what could it be like underneath? This surrealistic imagery stemmed from Judit’s post-traumatic state of mind as the traumas of World War II led many artists to return to the artistic tools of Surrealism, one of which is associative composition, the juxtaposition of numerus fragments, which can be playful or dramatic. Judit’s paintings have always been typically dramatic in their tone, which is apparent even in her pictures inspired by nature.

Finally, in the early 1970s, balancing between figurativeness and abstraction, the artist shifted towards figurative representation, while incorporating human body parts and anatomical details into her compositions, which were still primarily emotionally driven. A study trip she made lent much impetus to this change. Rome and Naples, Michelangelo and Pompeii confirmed in her mind that a dialogue with the past and the visual memories of the past can have a place in her own visual world.

Her series titled Michelangelesque was inspired by the great Renaissance artist’s representations of the human body. While the motif of the torso became increasingly popular in sculpture at the time, in Judith’s paintings it was the limbs missing from them – severed arms and legs – that came to the fore.

Europe celebrated the 500th anniversary of Dürer’s birth in 1971. Nuremberg paid tribute to the Renaissance painter with a large-scale exhibition of over 700 works, including nearly 400 by Dürer. This grandiose exhibition was a significant event for Judit and Péter. Judit spent years working on two large panel paintings, for which this exhibition, among other things, served as inspiration.

The pictures are teeming with organic forms, masks and human figures entangled in each other and squeezing each other out. Renaissance depictions of human figures celebrated man and the perfect body, while twentieth-century art revealed the monstrous and base sides of human nature capable of all things terrible: terror came to the surface, which the painter saw from close up and experienced herself. Her Roman Sarcophagus: Mantegna–Dürer Variations I–II lends expression to this recognition and at the same time marks the end of a period in her painting.

In the second half of the 1990s, human figures appear yet again in compositions such as Falling, Lava and Coal and Ash with muscular limbs as well as falling and swirling bodies pressing against the boundaries of the picture space. The apocalyptic tone of the scenes might well evoke the depictions of Hell in Last Judgement depictions, while referring back to the Roman Sarcophagus, completed two decades earlier.

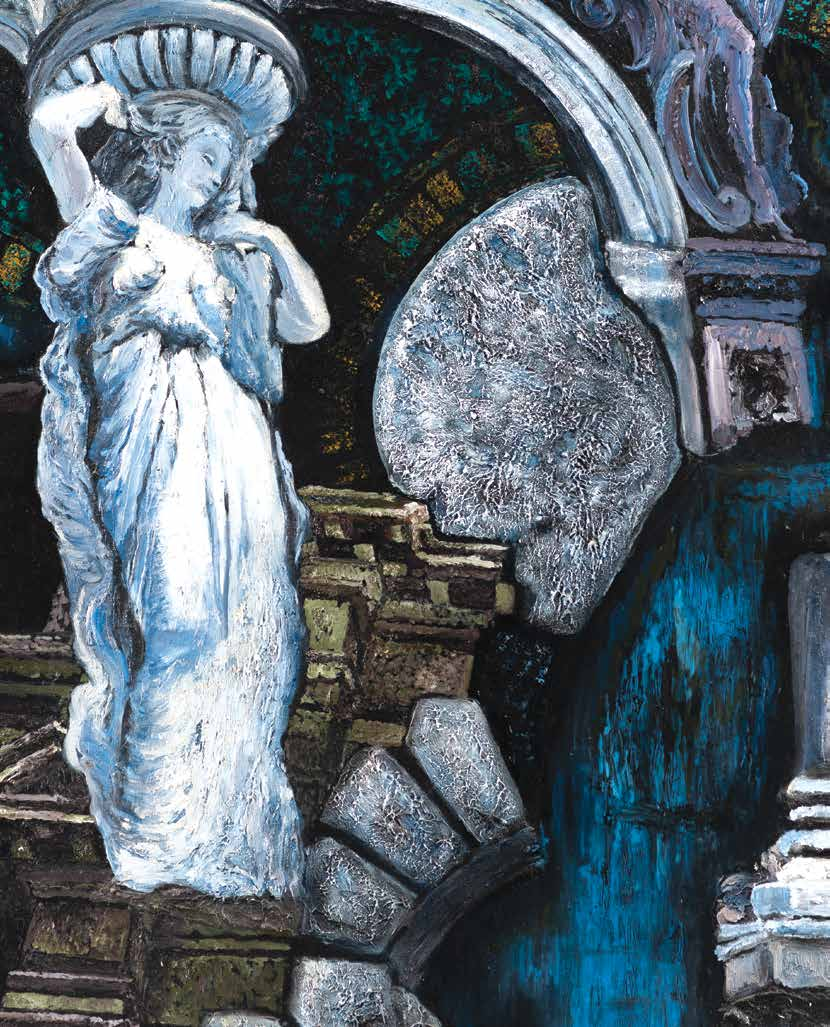

Budapest’s architectural image is defined by the historicising style, also referred to as ’eclectic’, which for a long time had a negative connotation but this slowly began to change in the mid-1980s, when art historians first recognised the values of the Secession and then those of historicising architecture, combining stylistic elements from various past periods. Predating this shift in approach, Judit Wellish Tehel discovered the values of the historicising architecture of her hometown, Budapest, in the early 1980s and her interest was primarily aroused by its building sculptures. The sculptural ornaments on the residential blocks and palaces followed antique, Renaissance or Baroque predecessors with caryatids and atlases flanking gates, as well as heads, masks and Gorgon heads often decorating the keystones. Over the years, the sculptures were damaged and defaced, leaving behind headless figures and distorted faces, which profoundly affected the artist, who returned to the city of her birth time and time again. In her first series inspired by this theme, titled Suffering Houses, we can see Michelangelesque sculptures clinging to the facades of the residential blocks of Pest, while the following pictures are more closely linked to the actual architecture. Abstraction is increasingly replaced by figurative representation, yet it is not living people but the secondary reality of heads and figures sculpted by stone carvers that become the models of these compositions. The painter breathes life into stone people and stone faces so that they can tell the stories of what they saw and experienced: the same things that the painter herself witnessed. These marred and disfigured sculpture-beings are silent witnesses of a period of terror. Decorative sculpture, which tends to be looked down on by ’high art’ is thus elevated to the role of protagonist: these building sculptures are capable of relating the terrors and tragedies dealt to the city in an authentic way. These antiquising male and female figures, these grinning faces or heads with gaping mouths, which evoke the frozen features of masks. No sound leaves these open mouths, yet we can hear their grievous cries. The houses indelibly bear the traces not only of World War II but also the fighting during the Revolution of 1956. The stone people, coming from antiquity, the Renaissance or the Baroque, are sometimes threatening, while at other times sad or proud: they are requisites of past eras of periods collapsing on top of each other; they are citations of citations. They are determined to stay strong and majestic despite their destruction and decay as they are the envoys of time who travel to and fro between the past and the future, while being relentlessly present.

The architectonic stories told by the artist are metaphors of her own experiences, as they brought her the certainty that her memories are real: these stones bear witness to what happened there. It is as if these lines from a poem by Attila József expressed Judit’s feelings: “In me the past falls like a stone / through space without a sound. / Away sways time silent and azure.”4 And indeed, her fragmented memories occasionally appear in colour – in yellow or in blue –, while at other times their tendency is towards the monochrome, with their grey stoneness speaking in more sombre tones. The sculptures that illustrate buildings become the postmodern players in the painter’s individual mythology.

The artist was fascinated by the material of stone and sought to transplant it into her painting. Using the tools of painting, she wanted to convey its qualities, its rustic surface, allowing her paintings, customarily not intended to be touched, to become sensory and step outside two-dimensionality thanks to their facture. In Norway, she discovered an industrial agent used for painting walls, which turns the surfaces it is applied to rugged and stone-like. Judit would often use this ’undercoat’ in some parts of her paintings: in some broad-stones or wall details. Her desire to achieve a richer facture and entering three-dimensionality soon appeared as a general trend in painting at the time.

In the mid-1990s, the artist was captivated by a new subject: Norwegian nature, with rockslides and water-eroded fields of stones. However, the pictures she painted at this time cannot be called landscapes in the traditional sense.

The most well-known mythical beings of Norwegian culture, Norwegian and Scandinavian folklore in general, are the trolls living in caves, forests and seas. It is believed that if a troll is exposed to sunshine, it turns into stone. Stones found in nature, shaped by its elements, may bear troll-like features resembling a foot, a hand or a nose. When the Norwegian world of stones seeped into the artist’s universe full of stone-fates and stone-memories of Budapest, it was not the aforesaid mythical beings that came to life in the stones of her paintings, but rather her attraction to stones, her empathy and affection for them, which looked for human life stories in this seemingly lifeless material, in its cracks and forms shaped by nature. Her new paintings were met with great success since the local people recognised mythical heroes frozen into stone in the rock formations so dear to them.

Judit had often travelled the beautiful lands of Norway before then too, but from that time on she started to look for motifs during her trips across Rogaland. One of the dramatically powerful spectacles of this region is Gloppedalsura, the largest stone scree in Northern Europe, full of landslide rocks created by nature’s anger5 when, ten thousand years ago, the glaciers melted away from Gloppedalen, leaving a moraine behind. The other favourite place where the artist looked for stones was the coast of Jæren in southwestern Norway, known for its regular pebbles.

Judit’s dual lifestyle, alternating between two countries, manifested in her painting too: for years, she painted architecture in Hungary, stone-fates shaped by people that decorated buildings, while in Norway she was inspired by nature, rock formations polished by water or other elements.

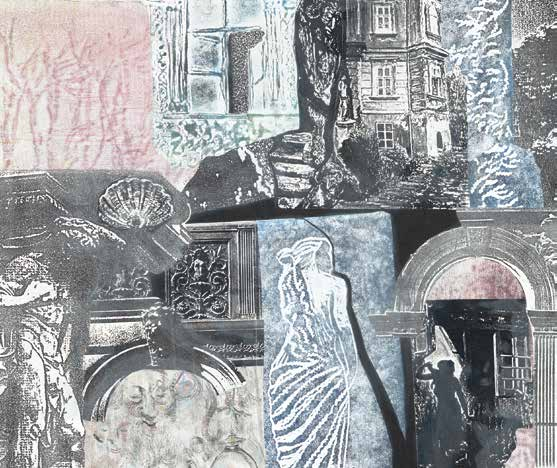

Besides painting, Judit Wellisch Tehel has a significant graphic oeuvre too. Since she often uses the method of constructing from parts, i.e. a collage-like technique in the composition of her paintings, it is no wonder that she loved to apply this in her paper works too. In her collages, the building fragments, gates and sculptures depicted from various perspectives form associative fields of memories. The emergence and spread of screenprinting and photocopying pushed the traditional graphic techniques increasingly into the background in the artist’s graphic work. Her six-part serigraph series Silent Witnesses (1988) was made in the graphic workshop of the Vasarely Museum in Budapest, and a copy of each serigraph entered the collection of the Kiscell Museum. In the next year, the series found a new life thanks to a photocopier in Stavanger, with its copies making their way into many private collections.

The art of Judit Wellisch Tehel is linked to European culture with many threads, while her painting cannot be clearly connected to individual intellectual trends. She travelled a lonely path. In her markedly emotional painting, she drew on the great eras of the past, its great masters, and this heritage served as an anchor for her to come to terms with and paint her own life and memories. She was influenced by Expressionism and Surrealism, and some features of her early paintings can be associated with the artistic aspirations of the CoBrA Group. In the first half of the 1980s, it became obvious that the simultaneous presence of different traditions created a unique cultural environment, allowing artists to move freely, reinterpreting, comparing and superimposing what surrounded them, what they had learnt and personally experienced. Judit Wellisch Tehel was at the vanguard of rendering these postmodern sentiments. The main tool of postmodern art was collaging, citations and juxtaposing different details. In the eclectic architecture of Budapest, its building architecture full of citations, the ruin-existence caused by World War II and the Revolution of 1956, Judit saw the potential for creating a personal narrative. And this discovery led her to her leitmotif: stone. Although the stones of nature, building stones and carved stones speak different languages, the painter has found herself, her life in them, similarly to how Ottó Tolnai writes in his poem I Stone:

“I like being called a stone

compared to a huge stone

I really do

I am a stone

a huge stone

I never thought of this

tho’ it would’ve been good

how many times it would’ve been good to

think

(…)

stone

I stone

I huge stone

how beautiful it is

god may also speak like this

stone stone stone stone stone stone stone stone stone

how beautiful this stone stone stone is“